On this page:

An Interview with Shann Ray

An Interview with Robert Meyerowitz

An Interview with Shann Ray

Shann Ray’s collection of stories

American Masculine (Graywolf Press), named by Esquire as one of Three Books

Every Man Should Read and selected by Kirkus Reviews as a Best Book of 2011,

won the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference Bakeless Prize. Sherman Alexie called it “tough, poetic, and

beautiful” and Dave Eggers said Ray's work is “lyrical, prophetic, and brutal,

yet ultimately hopeful.” Ray is a

National Endowment for the Arts Fellow and has served as a panelist for the

National Endowment for the Humanities, Research Division. Ray's book of creative nonfiction and

political theory Forgiveness and Power in the Age of Atrocity (Rowman &

Littlefield), was named an Amazon Hot New Release in War and Peace in Current

Events and engages the question of ultimate forgiveness in the context of

ultimate violence. He is the winner of the

Subterrain Poetry Prize, the Crab Creek Review Fiction Award, the Pacific

Northwest Inlander Short Story Contest, and the Ruminate Short Story Prize, and his

work has appeared in some of the nation’s leading literary venues including

Poetry, McSweeney‘s, Narrative, StoryQuarterly, and Poetry International. Shann grew up in Montana and spent part of

his childhood on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. He lives with his wife and three daughters in

Spokane, Washington, where he teaches leadership and forgiveness studies at

Gonzaga University.

Shann Ray’s collection of stories

American Masculine (Graywolf Press), named by Esquire as one of Three Books

Every Man Should Read and selected by Kirkus Reviews as a Best Book of 2011,

won the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference Bakeless Prize. Sherman Alexie called it “tough, poetic, and

beautiful” and Dave Eggers said Ray's work is “lyrical, prophetic, and brutal,

yet ultimately hopeful.” Ray is a

National Endowment for the Arts Fellow and has served as a panelist for the

National Endowment for the Humanities, Research Division. Ray's book of creative nonfiction and

political theory Forgiveness and Power in the Age of Atrocity (Rowman &

Littlefield), was named an Amazon Hot New Release in War and Peace in Current

Events and engages the question of ultimate forgiveness in the context of

ultimate violence. He is the winner of the

Subterrain Poetry Prize, the Crab Creek Review Fiction Award, the Pacific

Northwest Inlander Short Story Contest, and the Ruminate Short Story Prize, and his

work has appeared in some of the nation’s leading literary venues including

Poetry, McSweeney‘s, Narrative, StoryQuarterly, and Poetry International. Shann grew up in Montana and spent part of

his childhood on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. He lives with his wife and three daughters in

Spokane, Washington, where he teaches leadership and forgiveness studies at

Gonzaga University. “A man’s generational family line, his temperament, his response to abuse or violence or vacancy is embedded in a Western landscape as bleak as it is stunning, as fatal as it is filled with life.” ~ Shann Ray

Your book is titled American Masculine. Can you talk a little bit about American masculinity? Though it’s not monolithic, what parameters would you put around it? What are its strengths and challenges? How has it changed?

What are your thoughts on American femininity?

I’ll make an attempt at these first two questions together, in 2 parts.

Part 1

The loss of home is a recurrent theme in the literature of the American West. Sometimes downplayed or subdued, most often revealed as fractured or fragmented or wrecked, in Western lives the sense of subliminal grief is pervasive and painful and raises questions about the nature of men. What does it mean to be a man, and what does it mean to be a man in the West?

My father turned 70 this year. “I guess the Lord saw fit to bless me,” he said, and it wasn’t about the 70 years, it was about the wilderness. In a given season a Montana hunter might bring home a deer, perhaps an elk. Many people in Montana feed their families on the meat that arrives after an animal is rendered and processed. This season my father brought home two turkeys, an elk, two dear, two antelope, and a mountain goat, feeding a veritable passel of people including a family who advertised on Craig’s List wanting venison. The mountain goat he found in the Crazies, a hunt he took alone in the high country, cresting ridges and plateaus, rock walls and escarpments at higher than 10,000 feet. He went farther than expected in order to approach the billy from above.

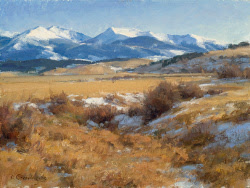

|

| The Crazy Mountains (via) |

He shot the animal behind the shoulder on a steep slant from 300 feet. The animal collapsed and slid down a narrow chute. It took time and caution to reach the place where the goat came to rest on a razor uplift of rock. There my father straddled a rock spine, stood over an expanse of sky and proceeded to bone out the animal. He knew he would need to work fast. In a pathless place, being caught coming down the mountain after dark is not pleasant. In his precarious position above the clouds, a job that normally takes my father 45 minutes took over two hours. With a hunting knife and a small bone saw he quartered the animal, removed the meat, and took the cape, head, and horns. Finally, with the sun leaning toward last light the heavy pack was ready and he began the descent. The Crazy Mountains are a dramatic and isolated “island” range east of the Great Divide, north of Big Timber. They lie in Sweet Grass County between the Musselshell and Yellowstone rivers. Just after dusk my father emerged on the flat below the mountains, made his way to his truck, and returned home.

For years my father and I could not express our weaknesses to one another. Nor could we easily express our tenderness. In those years conflict was hot and full of wrath and mostly irresolvable, but in later life, love came to us and taught us the nature of forgiveness. The physical landscape of Montana as well as the interior landscape of people give a small glimpse into the reality of how we ask for and grant forgiveness. The land often echoes how we change, and how we love. In the American West, as in America as a whole, we experience grief and loss regarding the masculine and the feminine. Many men do not have words for their relationship to women or to other men. When combined with a wordless or muted interior, the Montana landscape evokes an even more isolate and rugged exterior, often resonant of the stylistic characteristics of each man’s own physicality. A man’s generational family line, his temperament, his response to abuse or violence or vacancy is embedded in a Western landscape as bleak as it is stunning, as fatal as it is filled with life. The result for a man who cannot find words to express feelings is often a potent bend toward that which is either distant and apathetic or harsh, desolate, violent, and deadly. Such men live emotionally silent and lethargic or physically loud and largely defunct familial lives. In a dense shadow of their true selves they shun relational engagement by living in ignorance, apathy, or aggression toward that which is lovely and true in the lives of others. They are empty and void, and they are experienced as meaningless. In violence or apathy, men cut off the feminine and succeed in harming their relationships with women and other men. Even if it is a known truism that all men benefit from a healthy balance of the feminine and the masculine, many men find it very difficult to hold respect for the feminine within their own masculinity. Interwoven qualities such as courage and tenderness, power and love, mercy and justice, and transparency and boundary are necessary for the feminine and the masculine to relate on an in-depth level. To the meaningless man such qualities are beyond him. He is graceless.

Broken marriages, fractured families, the border of despair, the fall from grace. Men who reject grace or lack grace tend to live in either violence or ennui toward self and others. There is a hard fall for such men, and they remain severely broken. At the same time a deep desire to return and atone exists in the core of the masculine and in the men of the American West. In my experience almost all men yearn for oneness with the women and men in their lives. Without atonement and grace a life of sorrow and unwieldy consequence tracks a man, often in predatory fashion.

“The mystery of life and the hope for love is irrevocable and is felt even in men whose interiority can often appear more mountain-like than human.”

The mystery of life and the hope for love is irrevocable and is felt even in men whose interiority can often appear more mountain-like than human. Cold, massive in darkness or density, far removed from the intimacies of daily life, such men suffer. Yet in the heart of hearts I’ve found men crave something higher. If you have encountered wilderness, you know the awe and fear wilderness commands, and at the same time you know the intimacy wilderness imparts without measure. In a similar way, I believe the men of the West, even those who often appear the hardest or most emotionally void, desire a pathway toward grace, and if they find a way to set out on this path, they traverse the landscape bravely and with endurance. Certainly some never open their eyes or soul enough to journey back from a fractured sense of self and others to a way of life characterized by wholeness, yet those who dare are the men we know who are beloved in this world.

As men, we need women and other men. We need be restored to a true sense of home.

In order to do so, our will is required.

Kierkegaard said, “Purity of heart is to will one thing.”

Men who will atonement, embody manhood.

In my own home, because of my wife and the heart we share with our three daughters, there is a spirited love for poetry, story, music, and dance. When I met Jennifer I began to experience life more fully. She is an elegant and powerful thinker, a writer and reader who engages life with tenacity and belief in immanent possibility. A fully expressed person is a wonder to encounter—the woman or man capable of understanding, embracing, and transcending their own shadow while also attending to the light. Jennifer is such a person. I think of healing or wholeness as an everyday miracle: wholeness involves living not only in darkness, as we are wont to do, but also in light, as is our shared dream. In this light, with an articulated sense of the feminine and the masculine, we experience the sanctuary and generosity of home.

Home is a place of peace, reunion, and reconciliation, where love, discernment, depth, gentleness, wisdom, power, and care reside. Home, rather than dislocation or displacement, affirms the reality of what it means to be human. That home could be the original sacredness of the Native American traditions in Montana such as those of the Northern Cheyenne or the Blackfeet or the Sioux, or it could be a sense of home which heralds from a far homeland such as my own heritage in Czechoslovakia. Home is found in America, in the heart of the America we hope in and for which we openly seek a healing that will reverse the descent of the present and take us into the reality of a more responsible future. Home is acknowledged or embraced, challenged, attacked, or divided as a result of the level of privilege we have or the level of atrocity we have suffered in our families, nationally, or culturally.

There is a displacement of people today.

There is also the hope of returning home.

Emotional and spiritual wilderness can be as treacherous as physical wilderness. In the mix of Native American and Euro-American culture in Montana and in the American West, imaginative and essential life comes of care and discipline, brokenness and surrender, and the honoring of one another’s culture while also directly facing the atrocities of the present and the past. Honoring place and people and history with a commitment to truth-telling aimed at restoring the sense of relationship one to one, between people, and between cultures heals the nation. Of ultimate value is an understanding of love and power, the atrocities and massacres and grave harms, the pervasive human rights abuses as well as the reconciliations that have transpired in Montana history and in American history as a whole. In the concept of home and the lived experience of home, the nature of the masculine is often an unconscious weapon that is violently projected, rather than something that is contemplative, established in dignity and received with dignity. Listening is diminished or in fact destroyed. The healing of the masculine involves receiving the influence of the feminine, of home, and of the will to be honorable and intimate and authentically life-giving in the center of culture and country.

“I am reminded again of how silent and songlike and contemplative and prayerful the writing life is. Good art is an echo or counter-song of the authentic person and the embrace of life.”In a home where love and strength go hand in hand, grace and peace are the result, and here we are restored to mutual influence, personally and collectively. Such influence returns us to oneness and deepens our humanity as it generates reparation, restoration, and resolve. A true sense of home is not only mutual influence toward unity and respect, but more centrally, a true sense of home invigorates a more loving vision of our shared experience of life together. From here we build the bridge toward forgiveness-asking, toward making amends, toward atonement, and eventual reconciliation. In forgiveness there is peace, in justice the opportunity for reconciliation, and in atonement, love.

When my father came home from the mountains and gave to us from what he’d been given, my family received him with open arms. We ate well this year. We thought with gratitude of how he went at 70 into the heart of a rough and relentless country.

We celebrated how good it is to be alive and wild.

We gazed with open eyes on the wilderness of this world.

Part 2

One could say an extreme mediocrity exists in much of the masculine in America today, characterized by emptiness, impoverished relational capacity, an overblown or under-developed sense of self, and a life with others that is often devoid of meaning. Such men are filled of things like excess television, excess video games, excess sexual focus, emotional shallowness, and the man’s agenda at the expense of others. No words for feelings. Violence. Privilege for privilege sake, which results in decadence, and in the end decay, and finally death. The larger Western world, which in bell hooks’s terminology is inherently white, supremacist, and patriarchal, is currently experiencing this decadence, decay, and death. Carl Jung gave a clear and fear-invoking expression of the masculine and the feminine. In Jung’s conception the masculine is symbolized by the logos, which he referred to as the power to make meaning, to be meaningful, and to be experienced as meaningful by loved ones and by the collective humanity around us. Not the super-rational and in fact colonizing Western man, incapable of emotion and in fact regret, but a man who lives deeply, loves well, and is well loved. A question then rises, how many men do you know who are experienced as meaningful in their relationships with women, with their children, with others?

|

| Carl Jung (via) |

Jung conceived of the feminine as the eros, but not the blown-out glammed and glitzed porn culture of American media and overblown masculine agendas. Rather, he conceptualized the eros as the womblike existence that gives peace, the life-giving sacrificial essence willing to undergo almost anything in order to preserve life, the wild mystery at odds with all who might try to come against the child, the family, or the future. For me, Mochis comes to mind, the Cheyenne woman warrior whose ferocity is legendary. After the Sand Creek Massacre in the late 1800s in which US Cavalry slaughtered Cheyenne elders, women, and children and mutilated their bodies, Mochis took up the ax and fought as a warrior and killed many for eleven years until she was captured and shipped by train to Florida where she was incarcerated by the United States Army as a Prisoner of War. My mother comes to mind, with her bravery and her heart of forgiveness, and my wife with her vitality and fire. Not to mention my Czech grandmother. In our family, we call her the Great One.

|

| Mochis (via) |

Good poetry and good prose sees far into the mystery and depicts men who are often desolate, void, violent, and at odds with the feminine and in effect, at odds with themselves. These men, like myself, and many men I know, desire to move and change and become capable of giving and receiving love. Women are depicted as silenced or enraged, embittered, and critically at odds with the masculine. Women also desire an unfolding that results in unity over fragmentation. But to become humble sometimes requires being humbled. I know such women and men, whose shadows extend and do harm, and who are sometimes graced to come into a deeper and more redemptive love, and who have wept at the beauty that exists when they let themselves be shattered and let themselves emerge from that long darkness into something new. I hope to be with them when the dawn comes.

I am reminded again of how silent and songlike and contemplative and prayerful the writing life is. Good art is an echo or counter-song of the authentic person and the embrace of life. In response, the literary artist crafts poems and stories that show love and respect for the grand, ominous landscapes of the world, and in this landscape for women and men and families profoundly diverse in the interior life and the life of the collective. There has long been a philosophy that says the landscape, and people, grind you up and spit you out, so you better be ready or your head might get taken off. The mountains kill you. The animals kill you. Your family kills you. Life kills you. This seems immanently self-focused to me.

Yes, we are harmed. Yes, we die. We all know these truths. Yet it is good to encounter death with dignity: this we often miss. Just as it is good to encounter life with abandon, liberty, responsibility, grace, and mercy. I’ve felt deeply loved by the mountains and rivers and skies of Montana. There exists not merely the reality of our vain or vapor-like existence, but also the reality of life, enduring, perhaps eternal, and with it, an abiding intimacy in the world, despite and even within the presence of evil, decay, decadence, and death. Good poetry and prose does not ignore or forego or turn a blind eye to the presence of human evil, death, or decay. Rather, good writing reaches for light in the presence of evil.

This notion of an abiding intimacy, championed by Holocaust survivor and leading European psychiatrist Victor Frankl, leading feminist and social justice activist bell hooks, and many others, suggests something I find to be much more believable than cynicism, nihilism, and an overtly facile atheism: personal responsibility and collective responsibility are not only present in the world but paramount. How much faith does it take to believe life conspires against you and annihilation is the essence of existence? I think it takes a great deal more faith to convince myself death is the only way than it does to open my eyes to the inviolable essence of life, the dignity of others, the environment, and love itself. The experience of love, like the experience of a smile, achieves almost immediate affirmation of the existence of something more.

|

| Victor Frankl (via) |

Consider the eye. The eye, too, is self-transcendent in a way. The moment it perceives something of itself, its function—to perceive the surrounding world visually—has deteriorated. If it is afflicted with a cataract, it may ‘perceive’ its own cataract as a cloud; and if it is suffering from glaucoma, it might ‘see’ its own glaucoma as a rainbow halo around lights. Normally, however, the eye doesn’t see anything of itself.

To be human is to strive for something outside of oneself. I use the term “self-transcendence” to describe this quality behind the will to meaning, the grasping for something or someone outside oneself. Like the eye, we are made to turn outward toward another human being to whom we can love and give ourselves.

Only in such a way do people demonstrate themselves to be truly human.

Only when in service of another does a person truly know his or her humanity.A person is made up of logos and eros. Men and women who are over-masculine often seek to overcome, conquer and in fact overtake the eros instead of receiving the eros with respect, understanding, and distinction. Women and men who are over-feminine often seek to critique, control, or supress the logos instead of receiving the logos with openness, value, and good will. Masculinity in decadent America has lost its meaning and to recover or attain integration with regard to meaning, a return to the logos is necessary. The masculine must return to legitimate meaning in order to find healing. In America the feminine has lost a sense of wholeness, and a return to wholeness brings communal power. The recovery of the eros is the heals the feminine. In a decadent society we become easily imbalanced and when we are imbalanced we forward antagonism and annililation.

The ability to endure the suffering that produces greater love and greater life is common to women and men who have integrated the masculine and the feminine. Self-responsibility evokes collective responsibility, insight initiates good will, and through understanding one another, we love.

I believe the artist who serves humanity, knows humanity, and serves life.

I also believe the artist who serves life, serves love.

What would you say are some of the American West’s contributions to American masculinity?

Being from Montana I’d love to answer from that particular area of the American West and how it has contributed to American masculinity.

To grow up in a state whose name means mountain or mountainous is like living in a dream of wilderness in which you see a bald eagle atop an autumnal cottonwood over a wide river, the tree like a pillar of fire at the water’s edge, the bird glistening black and white, gold in the beak. Then you wake and realize it’s true, you did see that very thing, as I did on a recent drive through western Montana.

“To grow up in a state whose name means mountain or mountainous is like living in a dream of wilderness in which you see a bald eagle atop an autumnal cottonwood over a wide river, the tree like a pillar of fire at the water’s edge, the bird glistening black and white, gold in the beak.”I love Montana.

Montana has taught me to love the world.

I spent most of my childhood years in Montana, in various cities across the Big Sky country: in Bozeman and Billings, on the Northern Cheyenne reservation, and in high school in Livingston at the confluence of three mountain ranges, the Crazies, the northern line of the Beartooths in the Beartooth-Absaroka Wilderness, and the Bridgers. I practically lived in the rivers in the summer, jumping off bridges and floating the Yellowstone with my friends, the sun burning on our backs. The wildlife, the landscape, and the people gave me my sense of home. I love Montana people. So writing Montana landscapes, wildlife, and people feels natural, a way of honoring the gifts of growing up in Montana. The land unveils a deeper understanding of both love and power. People echo this understanding. This has in turn influenced my own understanding of the feminine and the masculine, and I believe in the larger scope of literature if we want to specifically consider the masculine, I believe Montana gives an honest, sometimes deadly, and ultimately restorative vision for American masculinity and world masculinity.

I believe the true test of legitimate love and power is one given by Robert Greenleaf, a former executive at AT&T, a Quaker and thought leader who was a contemporary of E.B. White and Robert Frost. For Greenleaf the true test of power is that others around you become more wise, more free, more healthy, more autonomous, and better able to serve the world. I’ve found soulful, strong women and men in every country I’ve had the blessing to work in, countries that range from America to Africa to Asia, and from Europe to South America. Often these women and men have emerged from profound heartache. They live with deep responsibility to others, and they hold forgiveness in their hand, even after experiencing grave human rights atrocities.

My first encounter with tough, soulful women and men, was in Montana.

In Montana, the mountains define us, as do the rivers, and the high plains. To me, Montana literature, like a good family, is home. As others have their loves, I have mine. Among the many abiding loves: A Fish to Feed All Hunger and Except by Nature by former Montana Poet Laureate Sandra Alcosser, The Big Sky and The Way West by A.B. Guthrie, Labors of the Heart by Claire Davis, Wallace Stegner’s story “Buglesong,” Wildlife and Rock Springs by Richard Ford, Thistle by Melissa Kwasny, The Triggering Town by Richard Hugo, Winter in the Blood and Fool’s Crow by James Welch, the story “Mahatma Joe” by Rick Bass, Beautiful Unbroken by Mary Jane Nealon, This House of Sky by Ivan Doig, We are Not in This Together by William Kittredge, Cheyenne Memories by John Stands In Timber, Another Attempt at Rescue by Mandy Smoker, and I Go to the Ruined Place, a collection of human rights poems Mandy Smoker edited with Melissa Kwasny.

Also, a chapbook of war poems by my grandfather’s brother John Ferch.

From those Montana writers I learned to love revision. Revision is a commitment to integrity, a resonant murmur of song and rhythm I believe in. In life and books. In life, revision is like atonement, asking forgiveness, reconciling, changing in ways that are meaningful to the beloved others in our lives. In writing, revision is the journey to make a work of art more whole, like a refining fire, a place of love and sensibility and torque and consequence, a place of grace that results in small wonders. Montana literature, a particular part of the literature of the American West, grants both desolation in great measure and the enduring light of human and divine consolation. In so doing, it points to the need for revision in men and women, as well as in our handling of the environment, and the beauty such recovery can give both to the land and to our families.

Montana literature is too big and exquisite and hardy and lovely for me to really comprehend. I feel the same about both the masculine and the feminine, and about Montana women and men specifically. Just as I feel the same about the varied regional literatures of America and the vast literatures of the world. I’ve felt loved and taken care of by the women and men who write from Montana. I’ve also felt a sense of legitimate and life-affirming power. In poems and prose, Montana writers paint an honest portrait of the men and women I know, in all our capacity for dread or dignity.

“Montana literature is too big and exquisite and hardy and lovely for me to really comprehend. ... In poems and prose, Montana writers paint an honest portrait of the men and women I know, in all our capacity for dread or dignity.”I’ve always been deeply moved by writing that is disciplined, beautiful, and capable of subtlety with regard to the human experience. For me, many of those whose work has become as close as family continue to influence me toward devotion to the heart of humanity and devotion to understanding the nature of our violence, our fear, and our hate as well as our forgiveness, our courage, and our love. Great art heals the heart and does so in ways that bear witness to who we are together and who we might become.

Montana has a distinct and rich literary tradition and features people as luminous as the mountains and rivers. There is bleakness, degradation, and desecration. There is also healing and light. You can’t be around Montanans (or immersed in a poem or story by a Montana writer) for very long without experiencing the heart of the wilderness, the personal fortitude required to give more than one takes, and the inner calm that comes of being in the presence of people who hold a quiet strength. Montana writers define my life like the mystery of a field of wildflowers, like the love of my wife, and the affection of my three young daughters. They are a form of living word, and they call me to a humble understanding of myself and others in all our complexity, devastation, and beauty.

And so, for me, the American West imparts honesty, hope, endurance, forgiveness, reconciliation, restoration, wholeness, vitality, and life to American masculinity.

You grew up non-Native on the Cheyenne Reservation. Then in high school, college, and professionally, you went on to achieve fame on the basketball court, which is important in Native American culture. Can you talk about the tension between being an insider and being an outsider?

The Northern Cheyenne reservation in southeast Montana is a place of strength and dignity and great humor. The reservation also bears the legacy of American atrocity. During the Sand Creek Massacre in the Colorado Territory U.S. Military led by Colonel John Chivington mutilated and desecrated the bodies of Cheyenne men, women, and children, then paraded the body parts in front of a raucous crowd at the Apollo Theater in Denver. Add to this, numberless experiences of genocide the Cheyenne endured in the wake of American colonialism. Miraculously, today among the Cheyenne there remains a tangible culture of resilience and a deep felt understanding of reconciliation and atonement.

|

| The Sand Creek Massacre, by Northern Arapaho artist Eugene Ridgely (via) |

My time there was formative. I was young and full of love for life and people and basketball. The experience of living as a minority, a thing Native Americans experience nearly all the time in the cities of Montana, was strange for me, fearful, and humbling and involved confusion, hard emotions, and numberless unique and often fearful encounters. Those early days resulted in lifelong friendships that have been extremely important in my life. When I think about my personal history I remember the rawness of the reservation. Fights, suicides, homicides. Unemployment. Drug use. Alcoholism. And I think of love, laughter, family, play, and generosity. Above all, there I experienced uncommon and nearly fathomless generosity.

We moved to the Cheyenne Reservation, like all the other moves, based on a coaching position my Dad pursued. We attended a tiny church there that was uncommonly strong and happy. At Plenty Coups he coached at the class C level in Montana, and at St. Labre on the Cheyenne rez he coached at the class B level. There were three white kids in the school, my brother and me and one other guy. Reservations are surprising: there I found more humor and life and friendship and love than I’d experienced anywhere. I also encountered untold despair. We witnessed so much grief and loss. We took part in anger and futility. People loved and hated. People died young. Many, many men and women died young. On the reservation, we were the shadow of America. We were America. We held immense love for basketball, and we played all the time, every recess, every lunch hour, every day before school and after school, the entire weekend. The court was outside, with chain nets. In winter we were in the gym, but any other weather it was outside on a blacktop with two big wooden backboards, the baskets set into the hollow of an abandoned U-shaped building. People played ball deep into the night.

We ate all kinds of good food. Tons of fry bread. Fry bread tacos. Antelope. Deer steak and pheasant, grouse and sage hens. Also chokecherry patties made from ground up chokecherries, mulched and mashed it into patties we let dry. Those patties were like cookies. We devoured them and drank them down with water. We joked and laughed like fiends and initiated each other in a culture by turns filled with joy and fierce with fighting. I had great fear in the beginning. In the end my fear was replaced by friendship. Lafe Haugen and Russell Tall Whiteman and Cleveland Bemint and Blake Walks Nice, Cheyenne, took me in and we played so much basketball it seemed to be the air we breathed. Lafe and I were inseparable. They called him Pepper and me Salt. I was also called Casper the Friendly Ghost.

God was present in sorrow and celebration, present in friendship and family.

Lafe and I were like a humor factory. People laughed and laughed just seeing us together, and when we left the room, more laughter came, and the familiar words, “There goes Salt and Pepper.”

I went back to Lame Deer, Montana, recently and gave a basketball clinic for many of the young Cheyenne athletes and spent time with many of my original friends like my best friend Lafe, along with Russell and Cleveland. Some ten or so years earlier, Blake Walks Nice had been stabbed to death behind Jimtown Bar just off the reservation, a reminder of our shared American heart of violence. It was good to be back and listen to the Northern Cheyenne culture and notice that some of those I knew as a boy had now become leaders in the community. Especially in my conversations with Lafe, I found one generation influencing the next, giving themselves as true servant leaders so the young could advance in greater health, wisdom, freedom, and community. The influence of those friends on my life is love and it teaches me to honor my own family, honor the songs and prose and poems that now attend my life, and honor the work I am given to be present to here and now. Along with all the despair that can accompany reservation life, there exists great personal and collective dignity, courage, love, and legitimate power.

When I finished the basketball clinic, Lafe approached me in front of all the young men and women athletes and their families. He wrapped me in a beautiful and colorful blanket. Once we were boys together. Now we were grown men.

“You are welcome here,” he said. “You are always welcome here.”

Wherever I go, his love goes with me.

Wherever he goes, my love goes with him.

You give a great class on writing characters of darkness and light. Can you explain what that means and what it is based on?

Your stories are dark and violent but with shining little moments of light. Wells Tower (“Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned”) feels that a writer has to put in a lot of darkness in order to earn moments of light. Is this a conscious balancing act on your part? Or is it less of a conscious choice, and you’re just drawn to those kinds of stories?

I’d like to try to answer the above two questions together too, if I may.

Reading a great short story is like walking on a ridge in the Beartooth Range in southern Montana, perhaps on Two Rivers Plateau or on the lip of the rock cirque above Hellroaring Lakes. You see the approach of a storm, a darkening above you that churns and moves, and suddenly you are struck by lightning. But you don’t die, you live. The burn you carry with you for the rest of your life is the imprint of that story.

Some real imprints for me are “Father, Lover, Deadman, Dreamer” by Melanie Rae Thon, “Labors of the Heart” by Claire Davis, “What You Pawn I Shall Redeem” by Sherman Alexie, “We Are Not In This Together” by William Kittredge, “Mudman” by Pinckney Benedict, “Lazarus” by Alan Heathcock, “Gold Star” by Siobhan Fallon, “Everything that Rises Must Converge” by Flannery O’Connor, and “The Three Hermits” by Leo Tolstoy.

A novel is a lifetime of rivers and mountains, landslides and forest fires.

Oceans. Suns. Night skies. Stars.

A short story is lightning.

A river after rain. A swollen river. Violent. Peaceful.

A poem is like the breath we breathe.

A galaxy. A solar system.

A single wildflower.

Ladyslipper.

Shooting Star.

The breath of God.

Poems, short stories, and novels: all three are beautiful.

They give us words that are like vessels to ferry the soul from this world to the next.

Stories and novels can be poems, and poems can be stories and novels, and in the cadence of Milosz from The Witness of Poetry:

What is poetry which does not save

Nations and people?

“Tragedy is love’s very sibling.”In my experience we are responsible to and moved by forces greater than ourselves. At the same time we often manufacture our own dignity or disgrace. I believe as men we borrow from the latent masculinity alive inside us, a place of blackness and fear that might in its self-shattering essence also be referred to as the terrifying abyss of which the modern nuclear age speaks, the same terror to which the contemporary age of slavery, sex trafficking, atrocity, and genocide is wed. The shadow, from Jungian psychology, comes to mind, as well as the recurrent torque of an ancient truth that states the sins of the fathers are handed down to the third and the fourth generation. Carl Jung’s work is luminous in this regard: in a true sense of mature intimacy, sex and feeling are unified, as are love and power as well as the masculine and the feminine. He said the more disembodied the shadow, the darker and denser it is, implying that in the disembodied man the will to exact punishment on self and others, both subliminal and overt, ascends like a mountain fire or drifts to an apathetic silence inhabited by men more dead than alive. In the sense of being alive to reality, acknowledging the darkness or evil that exists in us and others, we walk forward into an awareness not bound by cynicism or nihilism or atheism but affirmed in the courage and loyalty and hope that exists between the feminine and the masculine as well as between people, cultures, and nations.

The vastness of the wilderness in Montana and throughout the world finds an equally profound reverberation in the vastness of the human heart. There is intimacy in the wilderness, and danger, just as there is intimacy and danger in our small towns, our cramped trailers, our homes and sprawling cities. Are the invisible cities of Italo Calvino actually women and men and cultures? I believe such cities are the most lovely cities we know.

Many men and women have touched my life and made me more devoted to people, love, and art. Some have been like warriors or angels sent when I needed them most. I looked up and found them part of the poetry of life. The long history of healing that comes from poetry and prose is a cherished history. I think of Elizabeth Barret Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, and Robert Browning’s Men and Women. I think of C.K. Williams’s Repair and Mary Jo Bang’s Elegy. Desolation attends each of us, often more than we know. Our response is important. People whisper things to us, very quiet, very loving things, that change the course of our lives forever.

I love that you are a professor of forgiveness studies at Gonzaga. Can you talk about what forgiveness studies are and a little of their history?

In my work at Gonzaga University, a Jesuit school in the West, I teach in a doctoral program in leadership studies where scholars from the US and around the world gather to encounter what the Jesuits call the magis, the idea I mentioned earlier, that among many good things the ultimate good must be discerned and acted upon, and that cura personalis, or education of the whole person (heart, mind, and spirit) deepens the interior life of all humanity. Leadership is the study of personal, organizational, and global influence. My research in leadership and forgiveness studies seeks to describe the place where the personal and the global meet. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa comes to mind, as well as People Power 1 and 2 in the Philippines, the reconciliation ceremonies at the site of the Big Hole Massacre in northwest Montana, the Velvet Revolution from the Czech lands, and the work of people like bell hooks, Paulo Friere, and Martin Luther King Jr. Common research findings in forgiveness studies today show people with higher forgiveness capacity experience less depression, less anxiety, less heart disease, greater emotional well being, and the potential for a stronger immune system. The Labanese writer Kahlil Gibran echoed this sentiment by saying “the strong of soul forgive.” A courageous statement by him, especially when you consider the magnitude of the losses we encounter in his elegant and excruciating memoir The Broken Wings.

|

| Gonzaga University (via) |

I see grief as a beloved other whose voice we ignore to our own peril. I love Jung’s image of drawing grief closer in, drawing it close as you would a good brother or sister and listening to what it whispers in your ear. The immensity of the losses we face are difficult to understand in light of belief in a Divine presence. Yet persistently, in terrible harms that range from cultural genocides to the systematic abuses that occur in the life of the family, people open my soul again and again with the clarity and audacity of their courage. Here the Divine in them and in the world is affirmed. Often when I return home from my work as a family systems psychologist, one of my daughters will ask me “Daddy, did you cry today?” In a simple enduring way the immense and gorgeous heart of that question overturns the hold of atrocity in the world.

To continue in this vein, my personal background has helped inform my understanding of forgiveness. My mother grew up in Cohagen, Montana, and my father in Circle, Montana, small windblown towns on the Montana plains. My father is of mixed immigrant heritage, some German, some Irish, some Czech, the rest spread throughout Europe. My mother’s line is less dispersed. In fact, her parents were married in New York in the 1940s during World War II, her father of German lineage, her mother Czech. Amazingly, her parents’ marriage, filled of square dancing and ranching, card playing and good conversation, began during the very time period in Europe when Germany invaded Czechoslovakia.

Reconciliation is personal and collective.

My parents remain in Montana, in Bozeman now, having moved first from Billings to Colstrip, and then all the way to Alaska before coming back to Montana, to Billings then to the Northern Cheyenne reservation at St. Labre, and from there to Livingston during my high school years, then on to Bozeman when my brother and I attended college. Some time back on a visit to see them in Bozeman I was seated on the couch with my mother. Arched ceilings and oak beams lead to high, wide windows that look out on the Bridger Mountains and the Spanish Peaks, the view itself a reminder of the vast wilderness that is Montana and how thankful I am to have a good mother, a good father. After growing up in trailers the house feels like a small cathedral. My parents were the first in their families to attend college. In marriage they had struggled with each other and through some weighty decisions reconciled with one another after time apart, and from there they went on to make deep sacrifices toward my brother’s and my college education. I was happy for them, the life they had given us and the life they had built for themselves.

My mom was asking me about some of my research on forgiveness and touch, and I was telling her the stories of people—how they had hurt one another deeply, how they were seeking forgiveness, and trying to return to a loving connection. South Africa, Rwanda, Colombia, the Philippines, Northern Ireland, the Native American reservations in Montana, and throughout the U.S., so many places of human suffering and regret, and how in the face of grave human rights violations, forgiveness would rise and move to heal the human heart. I was thanking my mother for the forgiveness she gave my father some twenty or so years earlier, for how graceful she had been. Even my choice of vocation was in large part due to the integrity she and my father brought to our family. Not surprisingly, that day as we sat on the couch, the natural, true way she carried herself shone through.

After a pause in our conversation she looked at me and said, “You know, I’d like to get together with you and ask your forgiveness for the harms I caused you growing up.” She spoke the words openly, with a pleasant look in her eyes, a look of confidence and assurance. I have always loved that look, the way she carries herself with such strength even when dealing with things that are daunting, or cumbersome. Her power as a person is direct and gracious.

“That is very kind,” I said, “but I’ve harmed you too, Mom. I’d also like to ask forgiveness.”

On my next visit to Montana we went to dinner together and had an evening of forgiveness-asking.

How do academics contribute to or take away from your fiction and poetry writing?

In the academic life, as a professor and a psychologist, I have the honor to be in touch with people and with the research and writing of the doctoral scholars who come to Gonzaga to pursue a PhD. I also have the responsibility to learn from great thinkers, writers, and researchers the world over. This means I get to read exquisite philosophy, theology, psychology, and social science from multiple disciplines, and I get to spend time with people in the trenches, fighting for new and more peaceful ground. This contribution to my life let alone to the poetry and fiction I pursue, is immeasurable.

I see it as a gift from God. A gift that found me, as I never envisioned for myself the role of professor, or psychologist, or poet or writer for that matter. The work is humbling.

Switching gears, how do you get the writing done? You’re a professor and a husband and father, and you attend conferences and teach youth basketball, among other things. How do you balance everything?

I like to call it grace.

I am surrounded by lovely women, my wife, my three daughters not yet grown, my mother, my wife’s mother, and my Czech-American grandmother, yes, the very one we call the Great One. With my wife Jennifer our house is alive with conversation and music and dance, and the daily run is a high speed dash until at last the house quiets and we whisper love to each other and the house sleeps. This threshold of quietness is like a descent into darkness for me, a powerful and abiding darkness in which the light emerges in words and the rhythm of words and the poetry of sound that has as its melody the breathing of my wife and three daughters as they fall into their dreams. I sit at the desk and feel deeply loved because of the way my wife’s face is illumined by the light from the hall, and I remember when she spoke to me like an angel earlier and how I pressed my face to hers and felt the bones of her cheek against mine, the bones of her forehead and the orbital bones of her eyes, the kiss of her lips against the underside of my wrist. She kissed me to grant me life, and to ward off death, and so the writing begins.

“I believe people are essentially good and evil, with a tendency toward evil and an enduring hope for good.”

Do you have any rituals with your writing?

At night generally, from 10 to 1 or so. I like to carry a pen and a mechanical pencil in my pocket, both generally black with some silver on them, a reminder to me of shadow and light. I also like to carry a few pages of poems, and or part of a short story or a novel, with me throughout the day. These pages I open on those occasions that present themselves, watching my daughters’ dance lessons, waiting for them to finish guitar lessons, watching them while they play in the yard, while I lay on the floor in the living room, sitting on the couch next to Jennifer, or just anytime that comes up really … when I open the pages in those fresh settings it tends to give a clear eye for what to revise and how to go deeper into the language. I think it has to do with seeing people in motion in front of me and listening to how their bodies move and the ways they seek love and give love, the ways they spurn or celebrate or receive each other.

What are you working on now, if I may ask?

Poems, stories, novel, and nonfiction essays. Some science, generally forgiveness studies. Specifically on the front burner is a novel called Blood, Fire, Vapor, Smoke that features a love triangle involving the poet daughter of a copper baron, a young Cheyenne man renowned for team roping, and a physically imposing but impoverished white man who is a bull rider.

Who are your literary influences and why?

My influences include Sandra Alcosser, Claire Davis, Milan Kundera, James Welch, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Anne Sexton, Gerard Manley Hopkins, A.B. Guthrie, Dagoberto Gilb, William Kittredge, Victor Hugo, Richard Hugo, Richard Ford, Katerina Rudcenkova, Leo Tolstoy, Louise Erdrich, Leslie Marmon Silko, Sherman Alexie, C.K. Williams, and Mary Oliver. I love these writers, and many more, because they do what Albert Camus and Vincent Van Gogh asked us to do as artists and people: create dangerously, and embody the timeless truth that the greatest work of art is to love someone.

We as writers are all drawn to certain subjects that reoccur. What are those subjects for you, do you think? Why are you drawn to them?

Love, hate, violence, tenderness, mercy, grace, forgiveness, atonement, hope, light, landscape, the human heart, the soul, the nature of mystery, how people engage what they perceive to be God or anti-God, the role of nihilism, atheism, and dogmatics of all forms, the heights of human history, the abyss of human history, all the miniscule and expansive ways we live and the essence of what gives us gratitude, what breaks us, and what makes us generous, vital, and beautifully dangerous.

I’m drawn to these subjects because I find the transitory or vapor-like nature of people alongside the infinite or eternal nature of people a braid of transcendent splendor.

What else are you passionate about? Or what do you love?

My wife Jennifer, my daughters Natalya, Ariana, and Isabella, sacred words, sacred affections, friendship, fatherhood, brotherhood, sisterhood, devotion, discipline, joy, books, poems, novels, science, and basketball … and much more.

Are people essentially good, or essentially evil, or something else?

I believe people are essentially good and evil, with a tendency toward evil and an enduring hope for good. Light and love and life form the untamable Mystery that unites us and draws us to a more true sense of ourselves, in my opinion. The book of Daniel says it eloquently. To me, Daniel was speaking some bone level truths when he said of God: “He knows what lies in the darkness, and light dwells with him.”

As I see it, discerning that light in the darkness of this world is a necessary and severe mercy.

Buy American Masculine at IndieBound or at Amazon

Buy Forgiveness and Power in the Age of Atrocity at IndieBound or at Amazon

This interview was conducted via email.

An Interview with Robert Meyerowitz

Robert Meyerowitz is the editor of the Missoula Independent, an award-winning weekly paper in Missoula, Montana. He was the longtime editor of the Anchorage Press, in Anchorage, Alaska, and has also edited newspapers in South Florida and Honolulu, as well as serving as a foreign correspondent in Central America and the Middle East. He’s the author of numerous columns, articles, and essays.

Robert Meyerowitz is the editor of the Missoula Independent, an award-winning weekly paper in Missoula, Montana. He was the longtime editor of the Anchorage Press, in Anchorage, Alaska, and has also edited newspapers in South Florida and Honolulu, as well as serving as a foreign correspondent in Central America and the Middle East. He’s the author of numerous columns, articles, and essays.“Mars, the stars, the bird, the mountains—any one of these radically shrinks all the quotidian issues raised by the news. And I love that.” ~ Robert Meyerowitz

When we were talking about doing this interview, you said you’d like to talk about hope and the West. Why? What draws you to this subject?

I moved to Montana a year and a half ago imbued with hopefulness—my life will be better! The air will be clean! There’ll be cowboys and cowgirls and wildlife! Of course, you get to the promised land and discover you brought your same problems along with your clothes and books, but that’s another story.

At the time, I was coming from brief sojourns in Missouri and on the East Coast; before that, I’d lived in Alaska for 15 years, and briefly in Hawai’i—and I should say, I consider those places the West, too. I’d driven back and forth across the continent, horizontally, diagonally, and one of the things I felt distinctly traveling from the West to the Midwest to the East Coast is the way the built environment takes over from the natural landscape, enclosing me; so in a literal sense, the West feels more open, and more things seem possible. In particular, there’s the much greater possibility of being awed and humbled by nature. It’s that sense of the sublime, the same thing that Hudson River School painters such as Albert Bierstadt saw in the West in the 19th century and took back to the east on their canvases—what I’d challenge anyone not to feel as they drive south today from Anchorage down Turnagain Arm; “Look,” you think, “it’s the land that time forgot.”

|

| Albert Bierstadt's Mount Ranier (via) |

Now, people will line up for the opening of a new chain restaurant in Anchorage. But I think we also long to see the earth unaltered by our hands.

I felt that just last night, in fact, not long after dark, when I looked up at the stars from the deck of my house above Missoula, watching for meteors. I felt it when I watched the Mars rover landing a few weeks ago, marveling not just at our technology but at the otherness of Mars, and I feel it nearly every day these days when this one particular bird comes to visit me. Mars, the stars, the bird, the mountains—any one of these radically shrinks all the quotidian issues raised by the news. And I love that.

Do you know Frederick Turner’s Frontier Thesis, “the origin of the distinctive egalitarian, democratic, aggressive, and innovative features of the American character has been the American frontier experience. He stressed the process—the moving frontier line—and the impact it had on pioneers going through the process” (source: Wikipedia). It’s been critiqued since its presentation in 1893, but do you think this idea of frontier is still in effect today? How does it relate to hope?

Already, at the end of the 19th century, Turner was talking about the closing of the frontier, I believe, so by his lights, the frontier experience was all but over more than a hundred years ago. But that wasn’t quite true. Alaska came into its own in many ways in the 20th century and still thinks of itself as the last frontier. And Montana, for one, isn’t altogether settled still, in the sense that there’s a very real and unsettled debate about the use of its vast public lands. One way that you can see striking differences between the East and the West is by looking at a map of federal lands by state, like this:

|

| via |

More figuratively, Alaska is still a place where people go to reinvent themselves, and I think that also still happens to a slightly lesser extent in Montana and the West. I say “lesser extent” because Alaska is still at least physically remote. In the continental U.S., one of the signal qualities of frontier life was its remoteness. Lighting out for the territories then was almost like going to the Moon today. But today, people in Montana and Wyoming and the Dakotas are connected to the same internet as everyone else. You can’t outrun your past.

Yet the West is still being made. Compare that to, say, St. Louis, where people are fixated on where you went to high school, assuming you’ve lived your whole life there; the emphasis is on lineage and stasis and a kind of insider-versus-outsider debate. At one time, say, on the verge of Lewis and Clark’s departure from there, St. Louis was the most heterogeneous of cities. It was thriving and had no second-generation residents.

In the West, I think, people are less likely to discriminate that way. They can’t afford to, when so many of us are from somewhere else. We’re still more actively engaged in making a community from disparate parts.

The Wallace Stegner quote from which the title of the blog comes is “One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.” Stegner viewed hope as relating to society and cooperation, the opposite in his view of rugged individualism. Do you think his vision is true? What does that mean for today’s West?

It’s funny, that’s the second time I’ve heard that quote recently. The first time, it came from an aide to a Democratic congressman, who was explaining why compromise on legislation is in the Western tradition, contrary to the claims of a somewhat extreme environmentalist group, which labeled such action “collaboration,” and not in a good way.

I think Stegner was being wishful as well as descriptive there. I think it’s half true. In Montana as in Alaska, people like to say it’s the state’s way for people to help one another, because your neighbor is often the only one you can turn to when it’s 40 below and your truck won’t start, or your cows escaped the pasture. On an individual level, I think there’s something to that, although I’m fearful of claiming that folks are more neighborly in one geographic area than another. And in the West, the pull of individualism is equally strong. There’s a resentment of the federal government—of union—that smolders as it once did in the South, for a variety of reasons, and libertarianism is a potent political force, which is perhaps the opposite of Stegner’s ideal.

The West has a heavy literary burden, or boon, which is the Western. What is your view of the Western? Is it a thing of the past? Or would you expect its popularity to cycle with the times? What do you think is the legacy of the Western on modern writers of the American West?

When I read about Teddy Roosevelt in the Badlands, which I just did recently, again, in Roger di Silvestro’s book, I can see many of those legends being born and reified. But in some ways I think they’re bunk. They represent an effort to whitewash the past, and the truth, which is, for example, that many of the cowboys in fact were vaqueros, what today we’d call Chicanos, and they were looked down upon, just as the Indians in Westerns were stock characters and the cowboys and frontiersman were heroes, even as the frontiersman were taking the Indians’ land and doing much worse things to them. To be sure, there were atrocities on both sides, as, say, S.C. Gwynne makes clear in his wonderful account of the rise and fall of the Comanche nation in Empire of the Summer Moon. The truth, for me, so far as I can discover it, is much more interesting than the Western; the Western is a false-front house, and I need to tear it down to really see the continuous history of the places and the land. As for its legacy and influence, I think it’s in decline. It’s in the kitsch stage now. Which doesn’t mean I wouldn’t wear a good pair of Tony Llamas. I’d draw a line at the hat, though.

“The truth, for me, so far as I can discover it, is much more interesting than the Western; the Western is a false-front house, and I need to tear it down to really see the continuous history of the places and the land.”

You’re an adventurer, and you lived and worked all over the world. How does that contribute to your view of the West?

I was a war correspondent once upon a time, a foreign reporter, and that greatly shaped my view of the U.S. Before that I was sort of a reflexive leftist, subscribing to this totalizing, adolescent critique that the U.S. is evil and causes most of the evil in the world. But the truth as I discovered it was that many people can do bad all by themselves, and the U.S. remains a haven and an aspiration for many people in other countries, particularly in the kinds of places where I lived and worked in Central America and the Middle East. So I came back from abroad with a renewed appreciation of this country. It’s a subtle and profound thing, for me. Many more overt and public displays of patriotism make me cringe, but then, I’m a journalist. We shouldn’t be flag-wavers.

The West in particular is a mythic place for people from Jerusalem to Jakarta. In fact, the farther one gets from it, the greater its power that way, I suspect. I remember watching Dances With Wolves, which I thought was a silly, mythologizing movie, in the small Israeli community of Arad one evening during the first Gulf War. When I walked out with a group of Israelis, they told me they loved it, just loved it. How could they relate to it, I wondered? “Don’t you see?” one of them said. “We’re the Indians.” Oh. And then, I recall sitting with an old gentleman in his modest house in southern Spain, on the Mediterranean, where he had a black-velvet painting of a majestic moose, an animal I know so well from Alaska, which to him might as well have been a unicorn. I’ve heard cab drivers all over the world rhapsodize about Alaska when they learned I’d come from there, even though they’d never seen it. Their fascination reifies mine.

You’re a writer and a newspaper editor, which means you are on top of current events in a way most people aren’t. Do you think this makes you more optimistic and hopeful about the future of the West? Or does it make you more realistic, possibly pessimistic?

As journalists, our role is to be spectators at the pageant of what’s often folly. I don’t think our work typically gives us cause for hopefulness. Too much news in the conventional sense tends to make anyone pessimistic; if anything, it’s also our job to try to guard against that. Yet I’m optimistic nonetheless, because I think so many of the things I value about the West—the land and the wildlife—also constitute some of its capital, in tourism, and its drawing power.

Shifting gears, how do you balance being a writer with what must be a demanding schedule as an editor? How do you get your writing done?

Ha. I do it by saying to reporters, “Not now, I’m in the middle of a sentence!” But seriously, ultimately, my first obligation is to the reporters and writers I edit. I’m fortunate that I also enjoy writing, so I’m motivated to make time for it. And writing is a wholly different endeavor than editing. It’s not collaborative. It requires sustained focus. It gives me nourishment and joy. It’s kind of like tennis that way, for me—something else I make time for.

How do feature writing and journalism contribute to your other projects?

I think everything I do—and I only do non-fiction, for the most part—is no more elevated than feature writing or journalism. But then, I have a very high opinion of good feature writing and journalism.

May I ask what you’re working on?

I have two longer, simmering things, one about my time in Morocco long ago, when I was young and foolish and ended up in prison, and one about my collie Sally, who died last winter, and was my boon companion. I know, another dog book! Just what the world needs. But I do think there was something unusual about the way that dog and I blossomed together. And we explored the West together. In fact, moving to Montana was her idea. We’d drive through the state coming down from Alaska and she’d look at me with that unmistakable question: Can we stay here?

Talk about writers’ block. Is there such a thing? How do you get unstuck?

I don’t know. I’ve never had it. And the writers I work with can’t afford to have it.

Most writers have a couple of subjects they address over and over. What are yours? Why, do you think?

Other animals and history, to speak very broadly. Animals because almost all animal stories are about the hitherto-unsuspected powers of other animals, which is always exciting. This is true because we began by crediting them with nothing, and slowly have whittled away our definition of what’s uniquely human. There’s not much left. And I always like writing about something that’s known, yet isn’t, so that perhaps tomorrow a reader will see the same deer or wolf in a new light. History, because it always lend itself to narrative and reconstruction—to storytelling—and because the past is perhaps the real last frontier, constantly yielding new information.

What are you passionate about? What do you love?

According to YouTube, I’m passionate about ravens, collies, Aretha Franklin, Kate Nash, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Christopher Hitchens, Al Green, and Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers. If you looked at my bookshelves they’d tell only a slightly different story—more history, fiction and poetry, primarily. But all of these things are just cultural artifacts, right? I’m passionate about reading and writing and talking and serendipitous sightings of wildlife, and mid-priced vodka. I like people. I’m really lucky in that I get to work with smart, clever, imaginative people every day.

“I like people. I’m really lucky in that I get to work with smart, clever, imaginative people every day.”

Do we have reason to be hopeful here in the American West?

Yes. There’s always reason to be hopeful.

Hope is something you choose.

Choose hope.

(This interview was conducted via email.)